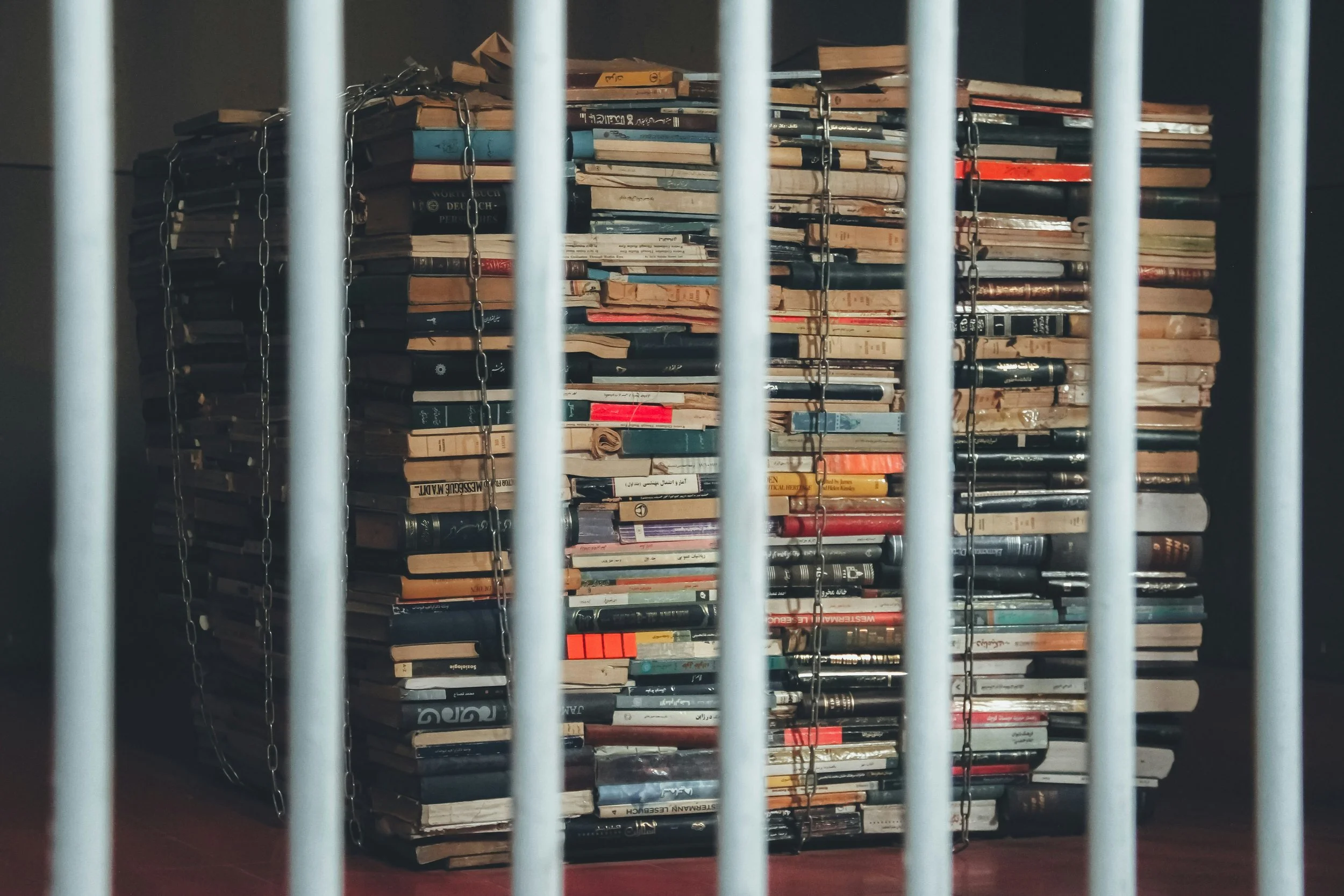

Censorship is so 1984. Read for Your Rights

image: Brendan Stephens for Unsplash

I’m writing this during Banned Books Week 2025. Tomorrow I’ll participate in an event I organized through my local library, a community read of excerpts from readers’ favorite banned books. I am looking forward to it. I live in a progressive town and my library has yet to have a title challenged, but it’s essential to me that we stand in solidarity with the libraries and schools across the country removing books from their shelves.

I almost don’t like the name Banned Books Week, because it sounds as if we’re simply highlighting the books that have been challenged or banned in the past or present. And while that’s a worthy endeavor (and the list is depressingly long), in truth it’s less about the books per se and more about deliberately excluding important characters and stories from our lives. Many of those characters are Indigenous, or Black, or Hispanic, or gay. Keeping their books from readers is keeping their voices from being heard, it’s keeping their very existence from being seen and acknowledged and cared about.

We’ll end up, if we’re not careful, walking down a city street comprised of shuttered buildings and boarded-up windows. There are still people in those closed shops doing and saying all sorts of marvelous things, but we’ll never hear their voices because someone decided that we can’t. Someone wants those shops shuttered to us forever.

When a book is challenged or banned, not only is someone dictating what other people can and can’t read, they’re also taking away one of the most powerful vehicles we use to relate to the world.

I’m not going to practice cultural appropriation here; I can’t speak to what this erasure does to the heart of a Black child or a trans person. But I can speak out of my own experience to the frightening connection between book bans and sexual assault.

Let me be clear: I do not think pornography should be part of any school’s curriculum. But the books being banned are not pornographic; in fact, they’re the opposite. Pornography often involves demeaning and degrading women. Saying, tacitly, it’s kind of all right as long as it’s hot.

Extremist groups are banning books in schools that discuss survivors’ experiences of sexual violence, rape culture, and even just information about the prevalence of sexual violence. Pro-censorship advocates falsely claim these issues are too “sexually explicit,” “controversial,” or “pornographic” for school.

image: Khashayar Kouchpaydeh for Unsplash

But here’s the thing. Books discussing sexual violence help us gain awareness about this epidemic and develop empathy for survivors. These books are powerful ways of storytelling and spreading awareness about sexual assault, while creating healing for survivors who share their stories. They help destigmatize sexual violence, bringing us together to bear witness to the stories about painful and traumatic experiences, and to allow us to be part of a collective demand for safety, healing, and accountability for sexual violence. Ultimately, these books help us move the needle toward creating a more informed, safe, and just world.

But banning these books signals there is something shameful and obscene in talking about sexual abuse, even though so many people, including students, have experienced it. These bans further stigmatize and legitimize silence around sexual violence, sending a message to survivors that what happened to you doesn’t matter, and an even broader message that silence about sexual violence is preferred over awareness about it.

A leading title in the book-banning pantheon is Speak, by Laurie Halse Anderson. The novel follows Melinda, a thirteen-year old girl and rape survivor, during her freshman year of high school. Parents, religious groups, and school board members want to remove books like Speak from schools and libraries, claiming they’re “soft pornography” or include “glorification of drinking, cursing, and premarital sex.” The “soft pornography” in question is the rape of a 13-year-old girl.

Let me repeat that: The “soft pornography” in question is the rape of a 13-year-old girl.

Rape is not pornographic: it is a violent crime. Are these people saying they’re turned on by this novel?

Banning books about marginalized communities tells people in those communities that they are not accepted. When these books are rejected by schools—and libraries—it parallels a feeling of rejection in the community.

I do want to offer some hope.

Despite the increase in book bans, important work is being done to counteract them. Online communities are centering discussions around banned books, encouraging reading titles that confront and expand people’s world view. There are new posts under #bannedbooks every day, bringing awareness to what is being censored and urging others to go out and buy them now. Organizations, like STOP Moms for Liberty, are forming to counter those that advocate against the teaching of LGBTQ+ rights, race and ethnicity, critical race theory, and discrimination.

Won’t you join them? Won’t you work to protect our freedom to read? There are a lot of ways you can help. (Every month I give new resources via my newsletter; feel free to subscribe at jeannettedebeauvoir.com, by just scrolling down to the bottom of the page.)

I’ll be honest: some of these books do contain scary or uncomfortable material, but that does not mean they should be kept away from the public. Life is full of scary and uncomfortable circumstances. People go through unpleasant, tragic, and downright terrifying experiences every day, and these characters, stories, and situations mirror the experiences that people have. And help us learn how to cope with those experiences.

G.K. Chesterton writes, “Fairy tales do not tell children that dragons exist. Children already know that dragons exist. Fairy tales tell children that dragons can be killed.” We all feel stronger when we know we’re not alone; for people going through trauma, these stories offer hope that the traumatic experience can be overcome. To my mind, a valuable lesson.

Or, hell—you can just decide that the rape of a 13-year-old is pornography. Up to you.

image: Jon Tyson for Unsplash